A dog owners guide to Elbow dysplasia from diagnosis to post operation

Elbow dysplasia is a common inherited orthopaedic problem in dogs where the elbow doesn’t develop properly. It particularly affects larger breeds, in our case a Golden Retriever, but Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherds and Springer Spaniels are also susceptible (Vethelpdirect.com). Hopefully any owner who has had to face this problem in their dog will find our experiences helpful, and the information useful.

This blog is an account, as owners, of our puppy’s journey with elbow dysplasia, from first symptoms to diagnosis and treatment, which, as I write in 2024, continues. It is not in any way a veterinary blog and is the story of one dog and his owners, hardly an indication of what to expect in every case. Nevertheless, such an account, had we found one, would have helped us to know what to expect, the longer than expected road to recovery, and the emotional rollercoaster that we have experienced. It may have helped to know that, eventually, the light that we kept seeing at the end of the tunnel that kept turning out to be an oncoming train, at some point would be the sunlight of relative normality for our pup.

It never occurred to me that our journey would be sufficiently eventful to be worthy of recording until we were quite some distance along the road. Fortunately, when taking our pup for an early vaccination I saw an invitation for participants in the “Generation Pup” project, a joint study between University of Bristol, and Dogs Trust, and I signed up. The contemporaneous diary entries of visits to the vet that I submitted, together with my Google Calendar entries, have been invaluable when recording the timeline of events. My wife’s memory of detail has been invaluable in reminding me of consultation discussions. Welcome to the owners guide to elbow dysplasia.

What is elbow dysplasia?

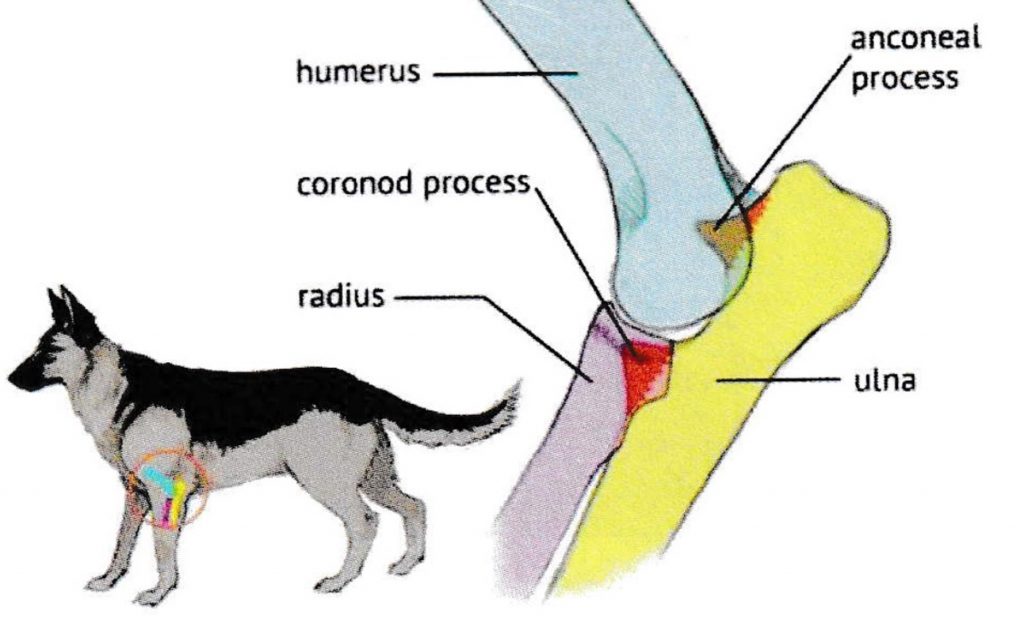

The following is my understanding of how our vet described the condition. The elbow is the joint where the humerus, the upper bone of the front leg, meets the radius and ulna, the two bones that form the lower leg. Elbow dysplasia is where the bones within the elbow joint fail to develop properly. Part of the elbow consists of a lump of bone, the “anconeal process”, fused to the end on the ulna, that help the elbow joint articulate, or bend. In some elbow dysplasia conditions this lump of bone does not fuse to the ulna, remaining “ununited”, the technical term being UAP – “Ununited Anconeal Process”. In Sam’s case, and I believe in many cases, the lump of bone did not fuse to the ulna because the radius grew disproportionately longer than the ulna, preventing the lump of bone from fusing with the ulna.

This is a necessarily brief overview of the condition. I’ve come across www.allyssamader.com which includes an “Owner’s Guide To Canine Elbow Dysplasia”, an excellent description of the condition, treatment options, and practical suggestions.

A bit about us

There are four of us in the household, my wife and I and two dogs, both Golden Retrievers, Ellie aged 4 and Sam, the subject of this blog, now aged four. We are fortunate to live in a rural location, one of a few houses along a country lane, surrounded by fields and footpaths, with many dog walks from the door. We have owned dogs for as long as we have been together. We found dog trainers 20 years ago, and still take our dogs for regular training. Both trainers have bred dogs. They are now firm friends and a source of experience and advice.

Choosing our puppy

In November 2021 my beloved rescue cross breed Tia died unexpectedly in her sleep, aged, we think, about 13. She had been my shadow for 10 years, and as far as I was concerned, she was irreplaceable. Whether dogs grieve is arguable, but there is no doubt that our two-year-old Golden Retriever Ellie missed the company of another canine in the household. She was less enthusiastic about walking, or indeed many other activities, and so by January 2022 my wife decided that it was time to look for a companion for Ellie. Since it was likely that a second dog would become “my” dog, it was appropriate that I should be involved. There was a conflict between heart and head. My heart wanted another cross-breed rescue, but with plans to purchase a motorhome following imminent retirement, something predictable was appropriate. Ellie is predictable, friendly with dogs and people, and generally relaxed about life, and so a decision was made to seek another Goldie. I opted for a male – they are loyal, and I was fond of a friend’s male Golden Retriever, full of character.

The advice from our training/breeder friends was to buy from a reputable breeder, choose a puppy with KC registered parents, each carefully scored to minimise the likelihood of inherited conditions, and that is precisely what we did. On 31st January 2022 we collected Sam, a cream Golden Retriever, from his breeder, already 3 months old because the breeder, very responsibly, refused to release his pups just before Christmas. Sam settled in quickly, was a dream to house-train, and was soon doing basic training at home, before joining Ellie at our dog training club, having a go at the simplest of activities for a short while, and socialising with other dogs. Sam was (and is) confident, friendly, and full of character. Our dog training/breeding friends agreed that we had made the right choice.

April 2022 – First signs of a problem

As soon as Sam had been vaccinated, we were out and about in the local countryside. We were strict with the 5-minutes-walking-per-month-of-age rule, and so we all set out together, one of us returning home with Sam after the desired distance. We sometimes walked with a neighbour and her dog, and since Sam’s recall was reasonably reliable within a few weeks, we allowed him off lead away from roads, and he quickly became one of the pack, a confident white bundle of fur happily running and playing with the two bigger dogs until it was time for him to turn for home, leaving the others to continue on a longer grown-ups walk. It was during a walk with our neighbour in April 2022, when Sam was five months old, that I noticed him limping slightly as he walked ahead of us. A few hours earlier Sam and Ellie had been running in circles over a cultivated field – maybe he had pulled a muscle, or some similar minor injury. I put him on his lead, and we walked home. For the next week Sam had short lead walks to rest the affected front right leg.

The limping continued, but thanks to the Easter break and available consultations, it was two weeks before we presented ourselves to a young vet to discuss the persistent lameness. She agreed that the lameness was probably a muscle injury, recommending walks of no more than 20 minutes daily, pretty much the limit for his age anyway, but these to be on lead.

We had already booked a holiday cottage in Scotland for the following week, and our walks were much more restricted in comparison to our normal practice. Sam continued to have a noticeable limp, and, on our return, we booked the first available vet consultation, on 16th May. We saw a different vet, who felt that, given the breed, the likely cause of the limp was elbow dysplasia, subject to confirmation by referral to an orthopaedic vet. Our hearts sank. My plans of long walks with Sam exploring the Peak District, as I had done with Tia, were not to be. We could only hope that the orthopaedic vet would diagnose something less serious. At least Sam was insured.

June 2022 – Diagnosis

Our referral consultation with an orthopaedic vet took place on 1st June 2022 at a branch of our own vets. The specialist visited the practice weekly, on Wednesdays, and this restricted weekly availability delayed some future consultations. To our disappointment, the vet confirmed that elbow dysplasia was the likely reason for Sam’s lameness. A CT scan would confirm this, but, he assured us, elbow dysplasia can be corrected with an operation, and there was no reason why Sam wouldn’t be walking for 3-4 miles off lead within four months.

We were offered an initial (cheaper) x-ray to check to eliminate the possibility of any other injuries, but we benefitted from the experience of a friend who was given the same choice to diagnose lameness in her spaniel – the x-ray failed to identify a hairline fracture and for her dog the delay in offering a CT scan resulted in a more involved and possibly less successful operation. We opted for an early CT scan for Sam, The only positive news was that, since elbow dysplasia cannot be cured by rest, Sam was free to resume of his off-lead walks, albeit restricted in duration because of his age. For the time being he could run free with Ellie and their canine friends.

The 8th of June, the date of the CT scan, was stressful. The vet had advised that if the CT scan results showed simple dysplasia, essentially a bone growth in the elbow joint, then this would be removed while Sam was still anaesthetised. We desperately hoped that this would be the case, and that, within a few days, Sam would be commencing a straightforward path to recovery, but this was the second occasion that this vet proved over-optimistic, since his reassurance that Sam would be walking off lead within 4 months eventually proved to be over ambitious. Maybe Sam’s condition was genuinely more complex than usually expected for elbow dysplasia. The vet called us at lunchtime. He would not be operating today – he had decided to submit the CT images to a specialist practice for a second opinion. We collected a rather sleepy and subdued post-anaesthetic Sam.

We had kept Sam’s breeder updated, and he requested a copy of the CT scan images from the vet. “Our” referral vet was unavailable when my wife collected the images, and she met with his colleague. I was at work when my wife phoned me with the result of the discussion, a call that I remember vividly. Two months after first noticing that Sam was limping, this second vet confirmed that the cause was elbow dysplasia, and he believed that it was inoperable. We would have to manage the pain, and in due course manage the inevitable consequential arthritis. Sam’s walks would be restricted for the rest of his life. I was devastated. At less than 7 months old, the best of Sam’s life was already behind him.

On 22nd June, 2 months since first noticing Sam’s limp, we met with the original referral vet to discuss the scans and specialist report. In addition to dysplasia, Sam had what the vet described as a “mild” radioulnar step in the front right leg. The two bones of the upper leg were out of alignment, the ulna not seated in the elbow as it should be. He could operate, and given Sam’s young age, the operation had a high chance of success. Sam would be running free within 3-4 months. I would never have thought that being told that my dog needed quite a serious operation would seem like such good news.

29th June 2022 – The Operation

The operation would involve removing the offending bone growth in the elbow joint. Cartilage on the bone surfaces damaged by the misaligned bones, would be scraped away. There was no guarantee that that this would grow back naturally, with inevitable consequential arthritis later in life, and so the vet recommended a stem cell injection into the elbow, in the hope that new cartilage would grow around the joint. Stem cells would be harvested from abdominal fat during the initial operation, grown in a laboratory, and injected in the joint at a later date. Our insurance did not cover this procedure, but Sam’s breeder had already said that he didn’t want us “out of pocket” because of vet fees, and he agreed to pay the cost of the stem cell harvest and injection, coincidentally the same amount that we had paid for Sam.

This all seemed quite invasive enough, but the vet had not finished. He planned to break Sam’s leg. The ulna would be surgically cut through, allowing muscle to pull the bone back into the correct alignment as the bone healed, so that all bones meet at the elbow as they should. We just had to trust the vet, and so we agreed to the operation for Wednesday 29th June. It is very unsettling to drop off your dog off at the vet to have his leg broken, and we were relieved to get a call that afternoon to confirm that the operation had gone well, even more relieved to collect Sam later in the day. Sam’s journey to recovery had begun.

First post operation weeks

I slept on the sofa that night, keeping Sam company, and to provide reassurance if needed, but in fact we both slept soundly. That night may have been stress free, but there followed 2 stressful weeks. Sam came home with a bottle of Metacam anti-inflammatory pain killer, and packs of Gabapentin to inhibit pain and relieve stress, a sort of “happy pill”. We found a “body suit” for Sam, of a design which only covered the affected leg, tied around his body to keep it in place. This kept the leg clean and stopped Sam from licking the stitches.

Within 24 hours Sam was back to normal. Normal puppy behaviour and a broken leg is not a good combination. Sam may not have been stressed, but we were, as we constantly stopped him from playing with Ellie, our older Golden Retriever, and from running around the house. We were surprised that his broken leg was neither plastered nor splintered, in fact with no support at all. We were subsequently told that the intact radius bone, parallel to the ulna, provided the necessary support, hence no further support was necessary.

The dog’s “toilet patch” in our garden is at the bottom of 5 steps descending from a patio, but Sam was not allowed to descend steps/stairs, and so we barricaded the top of the steps. Sam had access to the level patio for toilet purposes, but after months of training to use the lower gravelled toilet area, or wait until on a walk, Sam refused to relieve himself anywhere else. We resorted to carrying Sam down the steps, or if I was unavailable, my wife, led him gently down the steps by the collar. This arrangement remained in place for 4 months.

Entertaining the patient

We had a lively 8-month-old puppy, who was not allowed out for walks, nor any indoor exercise, and was full of energy. We had to provide cerebral entertainment, so that he tired himself out by using his brain. We benefited from years of attending training classes, and advice from trainers, and came up with the following ideas to keep Sam busy and out of mischief:

• We have a dog “activity game”, with drawers to be opened, cups to be lifted, and knobs to push to reveal treats. This worked to start with, but once Sam knew the options, it all became a bit frantic as he accessed the treats as quickly as he could.

• Treats balanced on paws or nose, the “Leave It!” for a few seconds before being allowed to eat the treats

• Basic tricks than did not involve walking or running – sit, down, stand. I would walk around him and step over him while he stayed still.

• Pick up a ball and place in a box (not very successful)

• Nose-touch of my hand or of objects

• Place his head on my knee when commanded

• “Sleepy” – head lowered to floor

• Identify and pick up specific toys (not very successful)

• Stand and hold a toy until told to “Give”

• Rolling over “dead” after I pointed a finger and said “bang”.

• Kong type toys, with treats to be retrieved by manipulating the toy.

Just a few minutes of these activities would tire Sam out for a couple of hours, but it was quite time consuming for us.

2 weeks post operation; Sam is allowed out and about

Two weeks after the operation Sam was examined by the orthopaedic vet who performed the operation, who was pleased with progress, and, more importantly, told us that Sam could already go on short lead walks, just 10 minutes three times daily – 5 minutes out, 5 minutes back. We are fortunate to live on rural lane, with walks in all directions from the door, but a 5-minute walk before turning back did not provide much variety. Turn right, through the field gate, just a few paces and return home, or turn left to the top of the Lane, cross the road, just a few paces and return back across the road to come home. We sometimes drove Sam to accessible routes so that he could spend 10 minutes in a different environment.

At least Sam was getting some physical exercise, but clearly not enough. In our home we regularly had to catch him as he flew past us doing “Zoomies”, sprinting around the living room, generally managing half a circuit before we fielded him and calmed him down. Managing a lively pup with an unsupported broken leg and recovering elbow was stressful. The vet had told us that that Sam’s broken ulna is supported by the adjacent radius bone, and does not take any body weight, hence no need for additional support, but there was still the healing elbow joint to consider.

2 months post operation; X-ray & stem cells injection

We had been led to believe that an X-ray two months after the operation should confirm that the cut ulna had healed, and Sam would be allowed some off lead exercise. Once again, the vet had been over optimistic. The incision was healing, but not healed. Once again, we were disappointed and frustrated; the end of the road remained far over the horizon.

While anaesthetised Sam’s right elbow was injected with stem cells, harvested during the initial operation, and introduced into the elbow in the hope that the cells develop into cartilage, replacing the cartilage worn away by the deformed bones during Sam’s formative months. We will never know whether this is successful. If Sam develops arthritis later in life, the stem cells may have delayed or mitigated the condition. If he remains arthritis-free, this may be thanks to the stem cell injection, or because we have managed Sam’s weight and diet to minimise the likelihood of arthritis, or, of course, a combination of stem cells and management.

2 months post operation and still ongoing after 18 months ; Physiotherapy

In August 2022, the orthopaedic vet referred us to a physiotherapist, who we already knew, since Sam was the third of our dogs referred to him over the last 10 years or so, and we had faith in him. He was always direct and to the point with his advice and recommendations, not always endearing himself to owners, but always putting the patient first. Details of individual consultations, initially weekly, but now every three or four weeks, will probably not be helpful, but a summary of how physiotherapy has progressed will illustrate the road that we have travelled.

During each consultation Sam is assessed by a short slow on-lead walk along the pavement or along a corridor at the clinic, after which the physiotherapist gives a gentle sideways nudge to Sams’s shoulders and hips to check muscle strength. Following the assessment, the physiotherapist applies a combination of infra-red and ultrasound treatment to hip and shoulder muscles and to Sam’s back, to reduce inflammation and encourage blood flow to improve healing. Sam has received occasional hydrotherapy, walking on a treadmill in water up to just above his hocks.

The aim of the physiotherapy is to improve the muscle tone to the front right leg as it healed, but just as importantly to increase muscle strength in the hips/rear legs to support mildly displaced hip joints, and to allow the rear legs to do their “fair share” of supporting and propelling Sam, taking the pressure off the front legs, a holistic approach to Sam’s body condition. I think that this is a fair summary. The treatment will hopefully also prevent future problems resulting from mild hip dysplasia, which Sam has also been diagnosed with.

Every patient is different, and the approach by physiotherapists will vary. “Our” Physio is cautious, aiming to build muscles before he “permitted” off-lead exercise, both in the interests of the dysplasia-affected leg and the hip dysplasia. In particular he encourages reduced activity in cold weather. We are aware that other physiotherapists are more relaxed, allowing off lead exercise between consultations quite soon after the operation, presumably subject to ongoing assessments. As weeks progressed we were increasingly frustrated that off lead exercise was discouraged, and eventually managed this ourselves, with just a few minutes off lead, very gradually increasing the duration, while preventing twists and turns when running. We monitored for any limping or apparent discomfort, and noted that our physio kept confirming progress despite this “extra” exercise.

18 months after the operation Sam continues to attend physiotherapy consultations every three weeks, covered by our insurance, for an assessment of progress, laser/ultrasound/hydrotherapy as appropriate, and recommendation for home massages and walking regime.

Hip Dysplasia? A sub-plot.

Many dramas have a sub-plot going on in the background. In this drama about elbow dysplasia, a sub-plot about hip dysplasia developed in the background.

We expected our first post-operation physiotherapy appointment at the beginning of August 2022 to be a straightforward planning meeting, to discuss the progress with Sam’s front right leg, and plan when to start physiotherapy. In what was to be a regular routine, the patient, Sam, was walked slowly along the pavement outside the practice. “What about that hip?” says the Physio. “What about the hip? Which hip?” we reply. “Did the vet not spot that weakness in the left hip? You need that hip to be x-rayed”.

This was not what we wanted to hear, but it is a sub plot in the main elbow dysplasia theme and so dealt with in a paragraph. Both hips were eventually x-rayed, and “mild” hip dysplasia diagnosed, a condition unlikely to cause major problems if Sam’s weight is controlled, and hip muscles toned by physiotherapy. The hips and back muscles were included in the elbow-related physiotherapy anyway since the weak right foreleg had caused an imbalance of muscle strength on the back legs. We knew none of this at the time of this initial assessment by the physiotherapist, and it was a body blow to discover yet another problem with Sam’s health, albeit one that turned out to be of minor significance.

“Mild” hip dysplasia is my term. The physiotherapist was concerned about the condition, but the vet felt that the condition is unlikely to cause problems. I suspect that hips either suffer from hip dysplasia, or they don’t, but in Sam’s case the symptoms are not sufficiently severe to have been diagnosed had we not had physiotherapy for elbow dysplasia, or at least that is the case at two years old.

2 months post operation and still ongoing after 18 months ; home physiotherapy

Following each physiotherapy consultation, we were given instructions on treatment at home, and duration of walks, building on the physio consultations to strengthen the muscles supporting the front right leg, affected by elbow dysplasia, muscles supporting the hips, and improving core muscle strength. The aim is to support the joints affected by dysplasia, and to balance the muscle strength across all four limbs.

Following the instructions of Sam’s physiotherapist, we massage the right front leg, lower back and both back leg muscles for a total of 10 minutes twice daily, and the healing elbow is gently rubbed, all following a routine given by our physiotherapist at the end of the previous consultation. Back legs are stretched while Sam is lying on his side, and Sam stands for a thirty seconds with first front and then back legs on a step, to improve core strength. I had to experiment to find ways to massage Sam without giving me chronic back ache, but Sam is very patient, particularly once used to the routine, and since he has grown taller I can massage while sitting on a chair, without the need to bend.

For the first few weeks we iced the right wrist and elbow twice daily for 5-10 minutes, holding flexible icepacks around Sam’s right elbow and wrist, which, with a wriggly puppy, could be frustrating on both sides. Eventually this treatment was limited to the elbow, and with some difficulty we sourced a suitably small ice pack with accompanying pouch and Velcro strap. We waited for Sam to sleep or rest on his left side and applied the pack to the elbow for the desired time, without fighting with Sam to keep him still. The pack, this time heated in the microwave, was also used when, in due course, heat had to be applied to the healing elbow. We were never able to source a suitably sized microwavable bag of grain, often used for human backache, and for a while heat was applied to Sam’s back using a hot water bottle, held in place with Velcro straps when Sam was asleep.

Massages and icing depend on a routine, or it gets forgotten – in our case Sam is massaged before each walk, and icing, when it was still required, was applied after the walk. Weather permitting, massaging outdoors reduced the amount of fur flying around the house.

2 months to 7 months post operation; Restricted walks

Months of restricted walking has possibly been the most frustrating part of the extended treatment following the operation. Sam has missed out on a lot of off lead experience, with no opportunities between 7 months and 18 months to run and play with other dogs. We were not able to train him outside the home or training classes, important when ensuring recall in the presence of distractions, scents, and freedom to run. We are fortunate to live in a popular dog walking area, with plenty of opportunity to meet and greet other dogs while Sam is on a lead, and Goldies are a breed that is naturally friendly and sociable, and so we have no socialisation concerns, but maybe such restrictions could cause issues with other breeds.

Sam was restricted to the house for two weeks following the operation, and from mid-July to mid-September, including recovery from the stem cell injection, was allowed three 10-minute walks daily. The vet then recommended that this could be increased to 3 walks of 20 minutes daily on an extending lead for further 4 weeks, after which Sam could be off lead for increasingly long walks. This was encouraging, but the physiotherapist, contradicted the vet’s advice, recommending three 15 minute on-lead walks daily – no off-lead walks for the foreseeable future. This was disappointing, but we favoured the advice of the physiotherapist, since he had successfully treated two of our other dogs in previous years and, unlike the vet, had spotted Sam’s “mild” hip dysplasia. We followed the advice of the physiotherapist to the letter, carefully timing walks using the timer app on our phones. The duration of the walks gradually increased, but always walking slowly. I had to vary the side on which side Sam walked, to balance muscle strength.

By December Sam was “allowed” two 50 minutes walks daily, the equivalent distance of 30 minutes at a normal pace, and we could walk both dogs together, albeit slowly with Sam on lead. We had a winter break in Cornwall, and on one particularly mild day on a deserted beach, of damp firm and level sand, we had a brief debate and decided to give Sam some freedom. To our relief he did not sprint away to run high speed circuits around us – he merely trotted around, occasionally running briefly, following scents and exploring. It was joy to watch, but it was a relief when we recalled him after 10 minutes and he came to us to go back on the lead. We spent the rest of the day watching him carefully (in my case almost with paranoia), but there was no limping or any other apparent after-effects. We did not enlighten the physio about Sam’s off lead fun.

A week or so later back at home, we decided to let Sam off lead again, this time in an enclosed field. Sam decided to ignore us, running at speed in circles over the rough pasture before eventually returning to us. To our dismay he limped home, dipping down onto his front right leg. He recovered within a day or so, but following this incident he remained on lead until a veterinary consultation at the end of January confirmed that Sam’s leg had healed, seven months after the operation. Again, the vet was happy with off lead walks of increasing length, whereas the physiotherapist recommended two 60-minute slow lead walks daily. We compromised by walking Sam on an extending lead.

Interestingly, when circumstances meant that walks were not as slow as recommended, and when we gave Sam brief off lead freedom, contrary to the advice, the physiotherapist noted that Sam’s hips had noticeably improved. We did not admit to breaking the rules, and in any case the improvement may have been due warmer weather at the time. I suspect that by this time Sam was stronger than many dogs who have not received physiotherapy.

7-10 months post operation; Returning to normality

7 months after the operation, in January 2023, we were compromising after differing advice from vet and physio, by walking Sam on an extending lead for the same distances as our other dog. We monitored Sam who showed no signs of discomfort, but at the end of each three weekly physiotherapy session, we were still told to wait until the weather was warmer and the ground firmer before any off-lead walking. By April, 12 months after first noticing that Sam was limping, the weather was mild, although the ground still soft and muddy in places. By now Sam was a strong and independent 18-month-old, but still with limited off lead training.

Each week we took both dogs to our training club, with Sam doing on short lead exercises, or those that did not involve running. When Sam was supposed to be lying or sitting in a “stay” exercise, the slightest distraction would cause him to run in circles around the training field, greeting each of the other dogs in turn, distracting for them, and frustrating for me, particularly since he would not be recalled, nor allow himself to be caught other than with the assistance of the trainer or other owners. Fortunately everyone was very patient since they knew Sam, and that he was restricted to lead walks and exercises. In the early days he was still on strong painkillers, which we think contributed to his short attention span.

We felt that it was time to allow Sam some more controlled off-lead activity during walks, and we began to let him off his extending lead for a few minutes in areas where he couldn’t run far, to practice recalls. This was initially stressful, worrying that he might undo some of the previous nine months of healing. We monitored him closely, but he did not limp. Within a week or so he was less likely to run around wildly, his recall was improving, and we gradually increased the off-lead walking, compensating by limiting walk distances to the shorter routes around our home. A portion of each walk was still spent walking slowly on-lead. We stopped asking the physiotherapist whether Sam should be allowed off-lead. During each session he noted that Sam’s muscle strength continued to improve. Sam was also calmer during training.

12 months post operation – back to normal

In August 2023, 13 months after the operation, Sam had his last post operation consultation with the vet, a physical examination, and an observation of him walking. The vet was happy with his recovery, and happy for his walks to be the “normal” 2-3 miles twice daily that is our usual dog walking routine. Longer walks should not be problem. If Sam is seen to be limping, then give Metacam to reduce inflammation, and limit walking for a couple of days.

Sam continues to have physiotherapy every 3-4 weeks and is massaged daily before walks. The physiotherapist is happy with Sams increasing strength – his only concern is maintaining muscle strength around Sam’s hips, although during a recent consultation our physio commented that he is very pleased with Sam’s progress. Sam’s front right leg is now full strength.

The vet has stated clearly that arthritis is likely in Sam’s right elbow at an age earlier than expected, maybe as early as four years old, irrespective of his current exercise regime, but this can be managed when (if?) it occurs. Sam has daily joint supplements with his food, and we control his weight by weighing his food portions. We desperately hoped that the injection of stem cells has resulted in a healthy elbow joint, that will remain free of arthritis for many years. However, now that he has passed his fourth birthday, he sometimes limps slightly in cold weather, generally just for the first few minutes of off lead walking. When we notice this, we give him anti-inflammatory medication – in our case Metacam, prescribed by our vet, just for a few days, and this seems to control any discomfort. It clearly does not affect Sam’s walks, still up to six miles a day over two walks, and he happily runs around with Ellie, our older Golden Retriever.

Final thoughts

After first noticing that Sam was limping, we have had a 15-month emotional roller coaster ride. The lowest point was when a vet, albeit not our own specialist, advised that Sam’s elbow dysplasia could not be corrected, and he was destined for a life of pain management and short walks. This was wrong, but we did not know that at the time. Life immediately after the dysplasia correction operation was consumed by managing Sam’s healing, with no real opportunity to worry beyond the following few weeks, but the following months were frustrating because the orthopaedic vet had been over-optimistic about the recovery period. We changed our veterinary practice during Sam’s recovery period. In addition, the caution expressed by the physiotherapist made it difficult to look forward to a time when Sam’s activity would return to normal. When you have owned dogs for many years, and now have a young dog, months of restricted walking contrasts greatly with the life envisaged for your pup. You meet other dogs of a similar age and must explain why yours is still on a lead.

For a while Mondays were a regular low point. Physiotherapy consultations were on a Monday, as were training sessions, and so after being told by the physiotherapist that muscles were still below strength, and walking must continue to be on lead, we then had a training session when Sam was difficult to control and was clearly behind his doggy peers in terms of behaviour and obedience. It wasn’t until we allowed Sam off lead for increasing periods that we began to look forward to a time when he would have a normal life, with Sam walking normally, albeit for short distances between lead walking, and his recall improving, essential for future normal walking.

Life now feels normal, but isn’t quite. I will probably always massage Sam daily, and we have the constant concern that Sam will develop arthritis at a relatively early age, which, if it happens, we will need to manage to maintain Sam’s quality of life. In training he is often better than some of his peers and is probably physically fitter thanks to ongoing physiotherapy. Sam walks off lead 3-6 miles daily, over two walks, and until beyond his fourth birthday Sam did not limp, even after a walk of nine miles (on a level canal towpath) and a seven-mile hill walk, both with the rest-breaks that we would usually have on such a walk. Recent occasional slight limping in cold weather is managed, only when required, by anti-inflammatory Metacam.

Life with Sam would have been a bit less stressful over the last 19 months if we knew then how things would be now, but of course there would never be any certainty. We are just grateful we are now able to enjoy life with Sam in the same way that we have with all our other dogs.